Australia Online: The Rise and Fall of Local Video Game Websites

Knowledge hub

Australia Online: The Rise and Fall of Local Video Game Websites

Mikolai Napieralski

This article traces the rise and fall of Australia’s homegrown video game websites, which emerged in the 1990s and early 2000s to serve a unique local audience during a time of regional gaming disparities. It explores their grassroots origins, cultural impact, and eventual decline as globalisation and changing technologies reshaped the gaming media landscape.

Grand Theft Auto 3 was the biggest gaming release of 2001. It was both a showcase title for the newly launched PlayStation 2 and a huge leap in open-world 3D gaming. There was just one problem. You couldn’t buy it in Australia.

The Office of Film and Literature Classification had banned it due to an unfortunate gameplay feature that allowed players to violently rob sex workers. And while an edited version would eventually see release, the ensuing drama took months to resolve.

But the only way you’d know this was if you visited the handful of local video game websites and forums that had emerged in recent years.

Looking back, 2001 feels like a lifetime ago. And in many ways it is. These days the world is a smaller, more connected, more homogenised place. But it wasn’t always like that. Back in the day there were real regional discrepancies when it came to video games. This disparity gave rise to a generation of homegrown websites dedicated to both the local industry and the idiosyncrasies that defined it.

Looking back, 2001 feels like a lifetime ago. And in many ways it is. These days the world is a smaller, more connected, more homogenised place.

This is the story of those sites, the people who made them happen, and how the arrival of a global, interconnected world would ultimately make them obsolete.

A HEAVILY modified Commodore C64

The internet as we know it today didn’t begin to emerge until the early/mid 90s. That’s when the World Wide Web (WWW) and Hypertext Transfer Protocols (HTTP) took online connectivity beyond the confines of science labs and provided the groundwork for a digital age. Early web browsers like Alta Vista and Mosaic soon followed, both cataloguing the online world and helping people find their way around it.

By 1995 a modest 20,000 websites existed globally. And if you’re of a certain vintage you may recall that ‘surfing the world wide web’ was a thing. Also, internet cafes. While this was all new and exciting to the general public, for a subset of tech nerds, it was part of a much longer journey.

As Alex Boz from AustRetroGamer explains,

“A lot of people don’t realise that many of Australia’s earliest gaming websites started as fan-run forums or Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) before evolving into fully-fledged media sites. Unlike in the U.S., where large corporations quickly dominated gaming coverage, Australia’s gaming scene was grassroots-driven.” [1]

One of these early online hubs, The Dungeon BBS, started life back in 1985 out of a Canberra bedsit. According to founder GeoffKM, it was powered by, “a HEAVILY Modified Commodore C64,” augmented by a couple of disk drives and two 7MB hard drives. [2]

There were many others, and this hodgepodge of hyper localised, fan driven BBS boards and associated forums led the online discourse throughout the late 80s and well into the 90s. But they required a degree of technical knowledge to access and interact with. Which meant they flew under the radar and were the domain of hardcore enthusiasts.

For the average Australian kid with a home computer or video game consoles, magazines were the primary source of information throughout the late 80s and into the early 90s. And most of these were imported from the UK or US.

Dial-up modems and static pages

By the early 90s Australia had two local video game magazines competing for readers - Megazone and Hyper . We’re going to focus on Hyper for the moment because they launched one of the first commercial video game websites in Australia.

If you use The Wayback Machine you can find the earliest capture of Hyper magazine’s Hyperactive.com.au dating back to 1997. It’s a simple, single screen layout and mostly exists as a home for the online forum. But it’s also an early indicator that local publishers were starting to turn their attention online.

That timeline broadly aligns with the US and UK markets, which saw the first commercial video game websites arrive in the mid 90s. According to Keith Stuart, a former contributor to Edge magazine and now video game columnist for The Guardian,

“1996 was the turning point. It was when both IGN and Gamespot launched (in the US). They had a lot of money and marketing behind them so it felt like suddenly this medium which had previously mostly been about video game newsgroups and fan pages was now a source of mainstream, commercial games journalism.” [3]

These US-centric sites would eventually launch local offshoots, and Gamespot was one of the first, with a dedicated local destination as early as 1999. But this was an outlier. And in the meantime, Australia’s own online revolution was quietly bubbling away under the surface.

AusGamers emerged from the primordial chaos in the late 90s (and is still running to this day). GameArena was launched off the back of Telstra’s BigPond gaming services in 2000 and ran for 15 years. Atomic was covering the local PC gaming scene from 2001 onwards. Vooks.net is a local Nintendo fan site that launched at the turn for the millennium and is still around. You also had unofficial hangouts like the WhirlPool forums .

These online destinations may have attracted early adopters, but they were limited by the slow and cumbersome nature of late 90s online infrastructure.

As Seamus Byrne, former managing editor at Kotaku Australia explains,

“Games coverage was still very magazine centred. Big glossy pictures, previews, and reviews because websites struggled to present games with all the energy and excitement that a magazine could. It's easy to forget websites were still pretty minimal on graphics, let alone video.” [4]

Y2K and the wild west

Australia’s internet was notoriously slow at the turn of the millennium, still relying on 56K dial-up modems.

All that would change with the arrival of wholesale broadband internet in the middle of the new decade. Faster internet allowed more responsive, interactive websites to supersede the static pages of old. This would become known as Web 2.0 and it provided the infrastructure for a new generation of websites to flourish.

Australia may have been late to the broadband party, but its arrival would see a burst of local websites in the mid 2000s. As Guy ‘Yug’ Blomberg, the co-founder of AustralianGamer explains,

“The frustration back then was the disparity between what we would read online and what the actual situation was in Australia. Rarely was a game released in Australia at the same time as the US, so you'd be reading these reviews for games you couldn't play yet - even finding details of when the game would come out in Australia would be a struggle sometimes. It was tricky to find a genuine local voice.” [5]

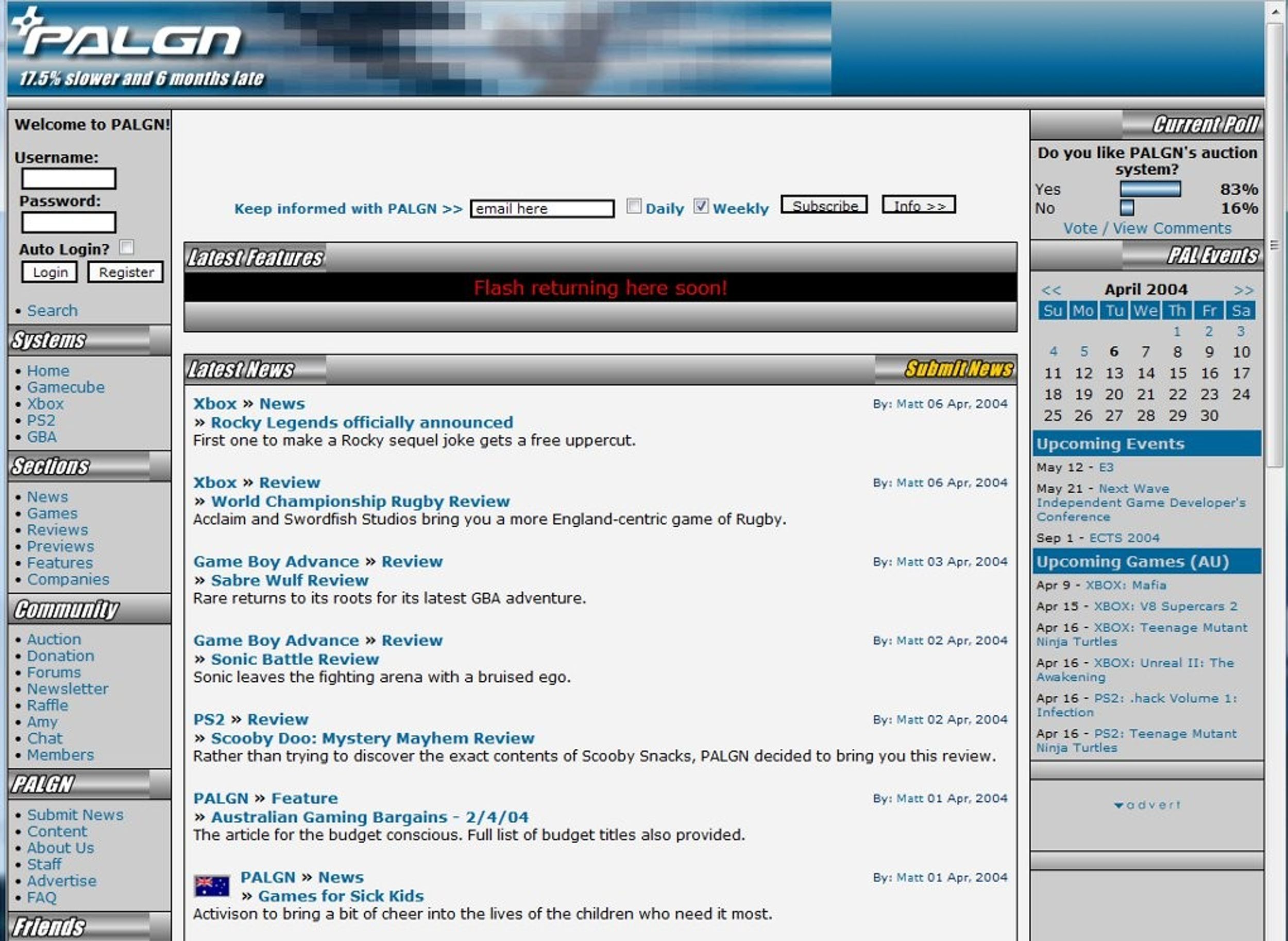

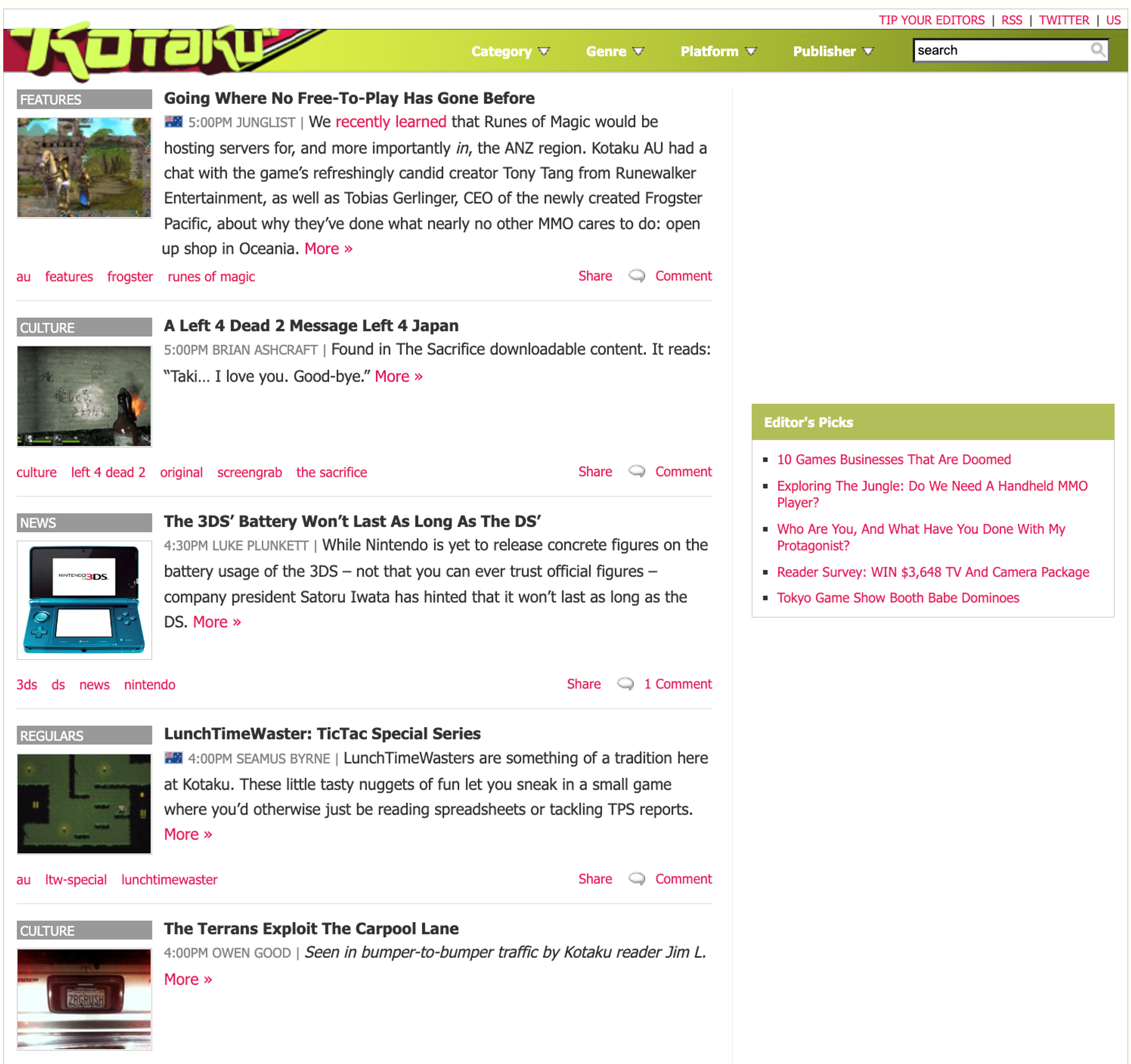

This obvious gap in the market saw several prominent sites appear that catered for a local audience, including PALGN (2003), AustralianGamer (2005) an updated Hyperactive website, plus locally licensed versions of international sites like IGN (2006) and Kotaku (2008).

Daniel Vooks has spent over two decades documenting Nintendo’s Australian presence for Vooks.net . Which means he’s had front row seats to the local scenes rise and evolution.

“It wasn’t until 2003 or 2004 that things really started to pop up [online] as magazines began to slow down,” he says. “After that, there always seemed to be at least a handful of local websites at any one time. People would run them for a while, drop off, and then another one would take their place.” [6]

Luke Plunket, who is based locally, but joined the international team at Kotaku in 2006, describes these early days as the “wild west.” As he puts it,

“It was much looser than it would become in the 2010s; games sites were just starting to come into their own and trying to find their own voice distinct from the magazines that most of us had grown up reading, one better suited to the always-online nature of the internet.” [7]

These Australian-run websites didn’t just provide a local news source, they also provided a local tone of voice and perspective. That’s something Mark Serrels knows plenty about. He worked at Allure media for several years, including a stint managing Kotaku Australia, where the daily routine could be be incredibly fast-paced.

“I published 8-10 posts, five days a week for about five or so years,” he says. “I think I published over 12,000 posts at Kotaku. Just ridiculous when you look back. There was a trick to it though. You had regular posts like, ‘What Are You Playing This Weekend?’ which took like 10 minutes.” [8]

Cash rules everything around me

If the previous decade had been all about tech nerds out on the fringes, the mid 2000s would see media and technology align to create a huge consumer market. Broadband internet, smartphones, and social media arrived in quick succession, forever changing the online landscape.

It was a golden era. It was also short lived. Because the local industry soon found itself dealing with several hard facts.

Let’s start with audience size. There’s no getting around the fact Australia is a huge land mass with a tiny population. This provides a natural ceiling on your readership. If you only have a handful of local websites it’s fine. But each new site splits the audience. And your audience size directly impacts your ad rates, which in turn impact your finances.

As long as the economy is humming along and people are throwing money about, all these rival websites can co-exists. But if a once-in-a-generation economic downturn suddenly crashes global markets you’re going to find yourself in a world of pain. Which is exactly what happened in 2008 when the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) wiped out the massive amounts of online ad spend these sites depended on.

Audience size and ad revenue are important. But they’re simply indicators of broader market forces. And as the 2010s got underway, fundamental shifts in both the video game industry and online space would upend the local ecosystem.

A thousand flowers

As the GFC faded from memory, the global economy became much more integrated. Blame social media. Blame cheap cash and low interest rates. Blame Obama. But the new decade would see a rapid standardisation of media, technology and culture around the globe.

What had previously been a patchwork of video game regions defined by their own TV standards, distribution systems and tastes became much more closely aligned. And Australia’s homespun video game websites found themselves reporting on an industry that looked very similar to the one in the UK, US, or Europe.

With everyone covering the same news, same systems, and same releases dates, the need for local websites simply wasn’t what it used to be. And as the audience numbers slid, so did the ad revenue, creating a race to the bottom. As Mark Serrels notes, there were almost, “too many local sites,” for a market Australia's size. [9]

Most of these websites wouldn’t last. While commercial pressures certainly played their part, a broader generational shift was also changing the online landscape. Kids raised on social media and YouTube influencers didn’t see the need for traditional blogs, forums and websites —let alone monthly magazines.

And so, one by one, the legacy websites faded from view. The indies that survived became more niche, media channels splintered off into countless shards, and when Kotaku Australia finally called it a day in 2024, it felt like the end of an era.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Because, at the end of the day, people want to share their hobbies and interests. They want to hear from like-minded people. And while the medium might change, the fundamental need for connection doesn’t.

Magazines were superseded by websites. Websites were nudged aside by social media. We don’t know what comes next, but our need to continue the conversation isn’t going anywhere.

As James Burns, editor of SuperJump - a local site launched in 2018 - concludes,

“Game technology will continue its forward march. What we play and how we play it will evolve in unpredictable directions. But our need to understand and appreciate this essential art form will remain. Games media, whether independent or commercial, will continue to play a critical role in this process." [10]

References

Notes

[1] Alex Boz interview. Forgotten Worlds (2025). https://www.forgottenworlds.net/australia-online-alex-boz

[2] Australian Bulletin Board Systems – BBS. ACMS forums (2023) https://forum.acms.org.au/t/australian-bulletin-board-systems-bbs/435/9

[3] How the internet killed video game magazines. Forgotten Worlds (2024). https://www.forgottenworlds.net/internet-killed-video-game-magazines

[4] Seamus Byrne interview. Forgotten Worlds (2025). https://www.forgottenworlds.net/australia-online-seamus-byrne

[5] Guy ‘Yug’ Blomberg interview. Forgotten Worlds (2025). https://www.forgottenworlds.net/australia-online-guy-blomberg

[6] Daniel Vooks interview. Forgotten Worlds (2025). https://www.forgottenworlds.net/australia-online-daniel-vooks

[7] Luke Plunket interview. Forgotten Worlds (2025). https://www.forgottenworlds.net/australia-online-luke-plunket

[8] Mark Serrels interview. Forgotten Worlds (2025). https://www.forgottenworlds.net/australia-online-mark-serrels

[9] Mark Serrels interview. Forgotten Worlds (2025). https://www.forgottenworlds.net/australia-online-mark-serrels

[10] James Burns interview. Forgotten Worlds (2025). https://www.superjumpmagazine.com

About the Author

Mikolai Napieralski

Mikolai is a writer, editor, and publisher based in Melbourne. He fell into the arts sector by accident and spent several years working with museums in the Middle East, where he developed digital content and edited exhibition microsites — including projects featuring Takashi Murakami and Damien Hirst. He later wrote a book about his time there: God Willing: How to Survive Expat Life in Qatar. More recently, he’s been looking at the lasting impact of video game magazines and media on a generation of (pre-internet) kids. You can read his anthropological take on old video games and print media via: https://www.forgottenworlds.net/