elekhlekha อีเหละเขละขละ

Knowledge hub

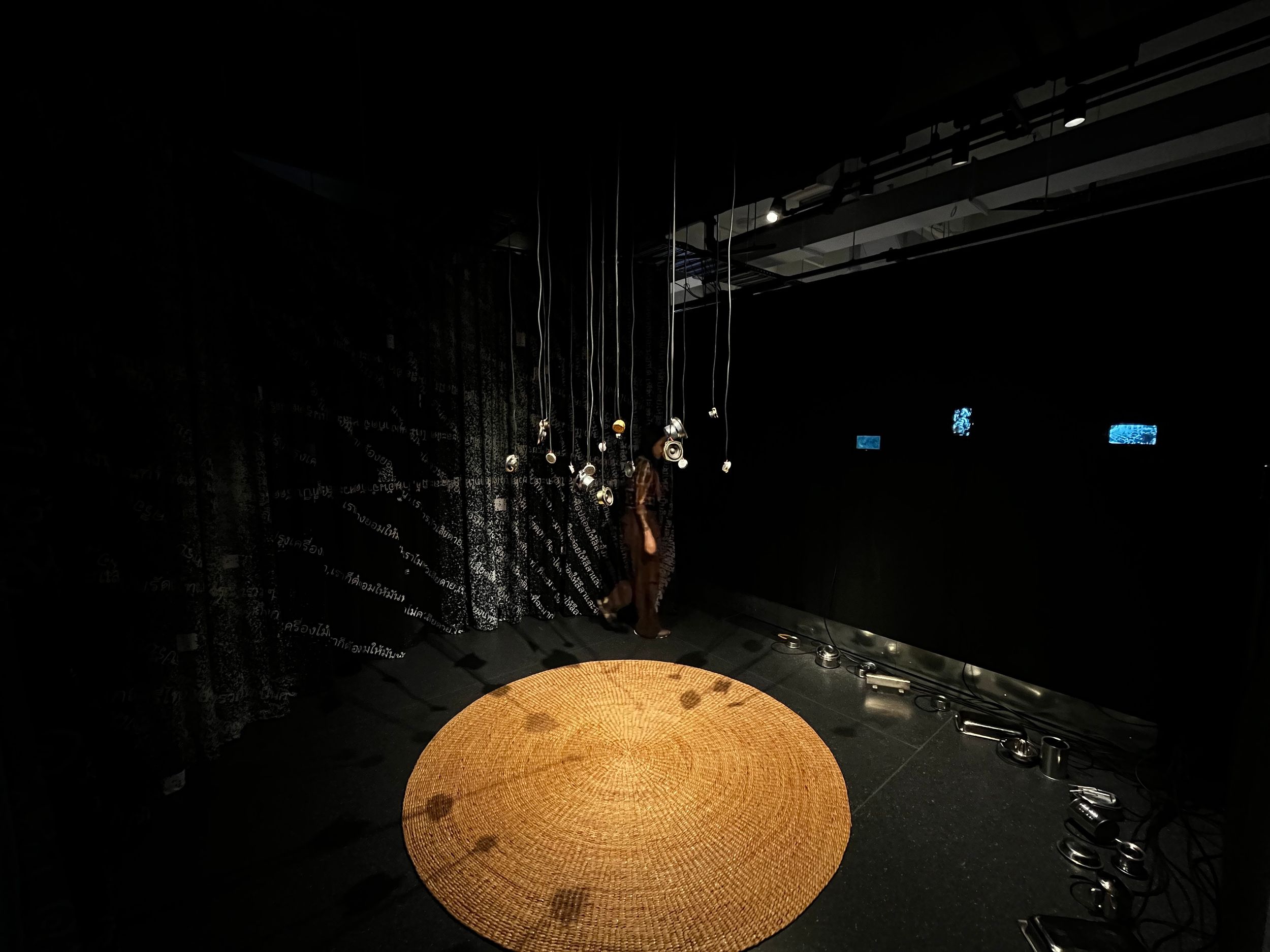

เสียงเพราะพริ้งรวมๆ กันเป็นกระจุกแต่อย่างเดียว (The beautiful sounds are all gathered together in one cluster) at NCM. Photo by Phoebe Powell

Project description

The beautiful sounds are all gathered together in one cluster, 2025เสียงเพราะพริ้งรวมๆกันเป็นกระจุกแต่อย่างเดียว

Found objects, custom software, mixed media

Commissioned by NCM

About the work

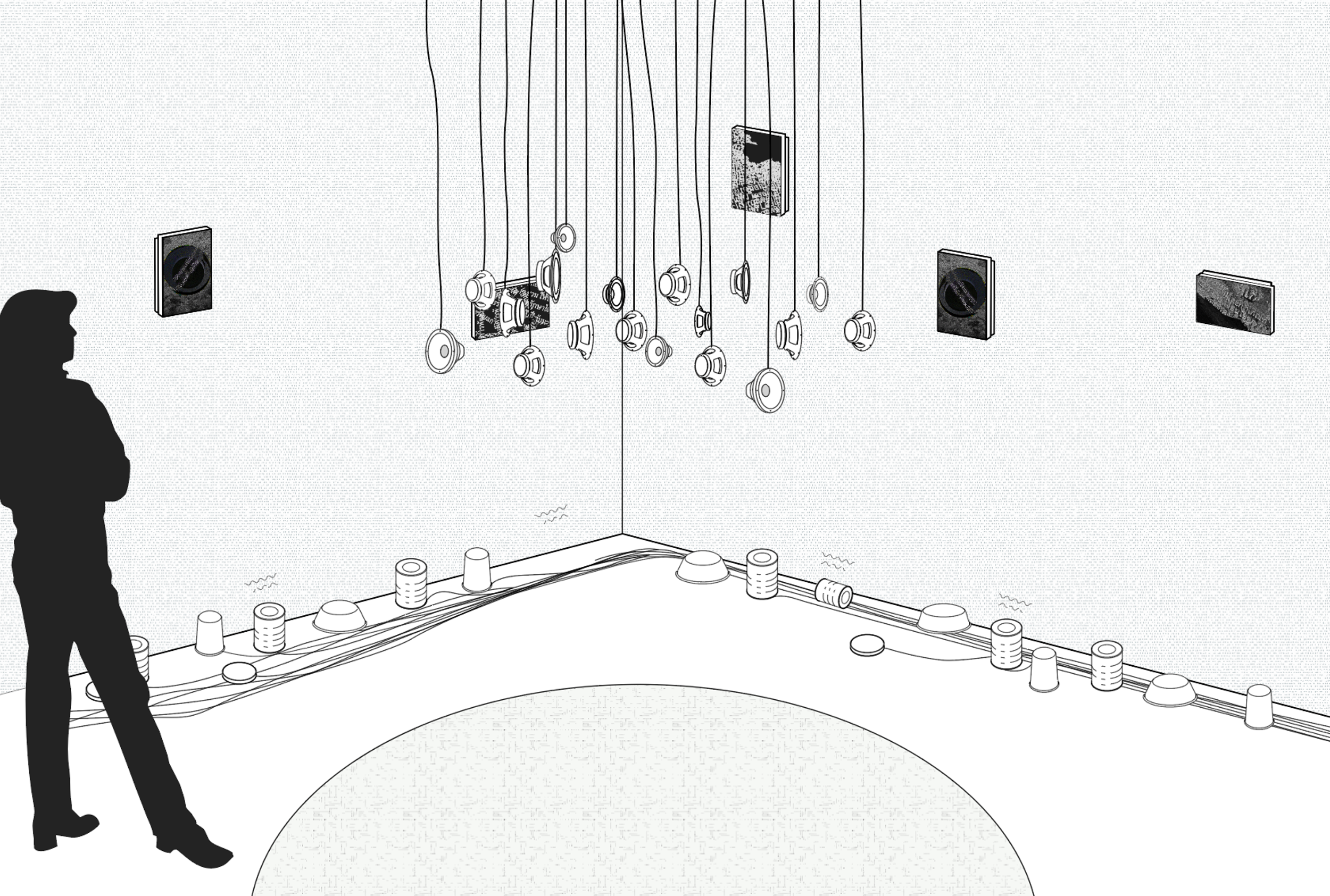

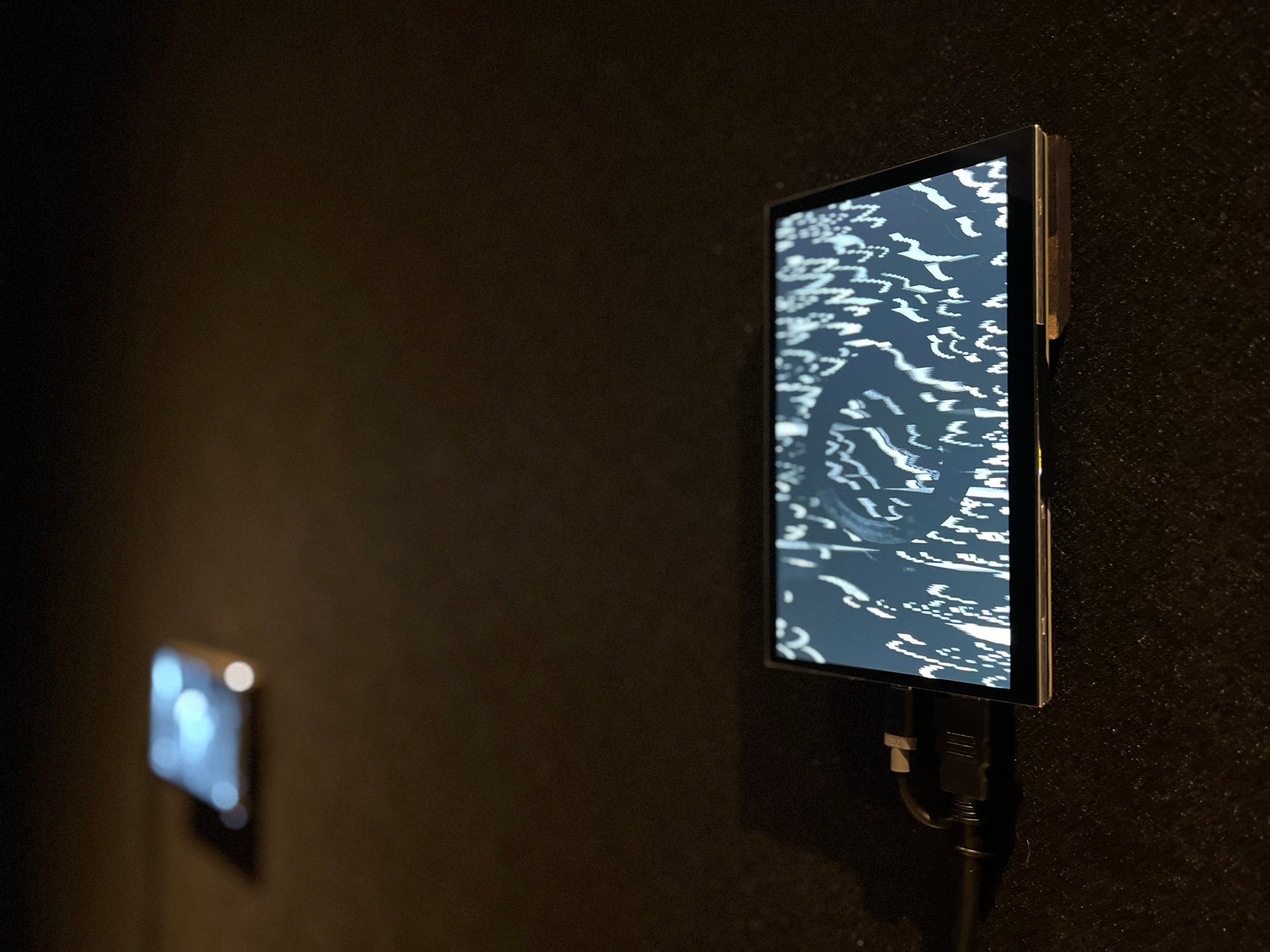

เสียงเพราะพริ้งรวมๆ กันเป็นกระจุกแต่อย่างเดียว (The beautiful sounds are all gathered together in one cluster) is a speculative ritual and durational multichannel visual and spatial audio installation that unfold across interconnected speakers, transducers, and screens. The sounds and vibrations echo a communal gong ensemble, while the audio-reactive visuals feature generative graphics created from prose by Thai writer and radical thinker Jitr Phumisak, displayed on small screens throughout the space. The spatial sounds and noises are a resynthesis of gongs and musical frequencies drawn from Southeast Asian minority sound cultures, such as Karen from Myanmar–Thailand border, T'boli from the Philippines, and Punong from Cambodia, intertwining with the Khong Wong sound culture from Thailand. (see frequency data here)

At the heart of the installation, clusters of small speakers and transducers interact with found objects, forming a complex sonic tapestry that may initially be perceived as mere noise from a distance. The layers of sound invite viewers to move closer to uncover the unique connections between each "gong," recognising that every sound—each vibration—contributes to a collective experience. Thus, the role of the audience becomes central; their active listening transforms passive observation into a participatory act of unlearning and relearning.

The title เสียงเพราะพริ้งรวมๆ กันเป็นกระจุกแต่อย่างเดียว (The beautiful sounds are all gathered together in one cluster), borrowed from Jitr’s writing, embodies dual meanings. One sarcastically critiques the dominant centralisation of Siamese court music, which often marginalises the rich diversity of ethnic musical practices, while the other celebrates the collective strength found in togetherness. [1] This duality underscores the importance of cultural identity and community within Southeast Asian musical practices, juxtaposing them against the backdrop of the cultural construct of the modern nation-state and the creation of otherness. [2]

"Community gathering gong ensemble is communal and collaborative; its form is hypnotically repetitious, with melodies and rhythms spread out among the players using the hocketing technique in which a flowing line is distributed among all the musicians." — David Toop

Highlighting the asymmetrical power relations between the global south and the global north. The piece delves into the notion of noise—historically, in the discourse surrounding Southeast Asian music and sounds, described as "absolutely nothing but noise," [3] from the inharmonicity found in Southeast Asia instruments such as tuned gongs and tuned wooden bars to minorities and marginalised folks' way of life clashes with conventional standards, modern nation-state authorities, and borders. The work reflects on the disappearances and silencing of activists, radical thinkers, and community leaders – folks like Jitr Poumisak, who were seen as outsiders and later a threat to be eliminated by Thai authorities. The piece embraces noise in the generative composition and physicality of the material. These sounds, voices, and ways of being are frequently labeled as noise, in contrast to what is considered a signal. But what defines noise versus signal? Who establishes this hierarchy, and why is noise often deemed undesirable?

Through this immersive experience, เสียงเพราะพริ้งรวมๆ กันเป็นกระจุกแต่อย่างเดียว (The beautiful sounds are all gathered together in one cluster) invites the audience to engage deeply with the sonic landscape, reflecting on the silencing of marginalised voices and the potential for noise to signify resistance, identity, and resilience. In this space, every sound matters, and together, they form a celebration of collective existence and the complexities of cultural expression.

Note on Sound Cultures

Sound cultures encompass the intonation diversity and diverse systems through which communities collectively understand and engage with sound. This approach acknowledges the multiplicity of sonic wisdom practices.

In contrast, references to "the tuning system" suggest a singular, fixed structure, standardised method of knowledge transmission based primarily on calculation and theoretical frameworks. Such terminology can inadvertently marginalise various cultural dimensions of sound and alternative methodologies of sonic knowledge, including aural and oral traditions, sonic rituals, and community-based practices of passing down.

Sound in many cultures serves multifaceted purposes beyond entertainment or aesthetic appreciation. It functions as accompaniment for daily activities, signals important alerts, marks the passage of time, coordinates communal labor (such as rice pounding), facilitates spiritual communion, and supports syncretic religious traditions. These functional and spiritual dimensions of sound represent essential aspects of cultural heritage that deserve recognition and preservation.

The Regenerated Sound Cultures

Through digital reinterpretation of traditional sonic elements, the installation creates a space where cultural heritage becomes dynamic rather than static—challenging conventional preservation approaches that often freeze traditions in time. This digital-traditional synthesis becomes itself a form of resistance against cultural erasure.

Note on Found Objects

Despite many communities losing their gong, whether from war, financial hardship, restriction of free movement between states [4], etc., the practice continues through DIY-found object gongs re-tuned with what they can recall from their collective memory passed down via oral/aural history. Some community like Karen ปกาเกอะญอ make their instrument out of recycled material made from trash [5] (i.e., Motorcycle brake cable)

References

[1] Jitr Poumisak จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์, “A collection of poetry and literary criticism by political poets รวมบทกวีและงานวิจารณ์ศิลปวรรณคดีของกวีการเมือง” and “Cementary of Thai Music หลุมฝังศพของดนตรีไทย”

[2] Thongchai Winichakul, “Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation”

[3] Terry E. Miller and Jarernchai Chonpairot, “A History of Siamese Music Reconstructed from Western Documents, 1505-1932”

[4] Yasuhiro Morinaga, “Encounters with Asian Gongs: A Fieldwork Travel Journal” and Aural Archipelago, “Canang Situ - Gong and Sardine Tin Ensemble of Southwest Aceh”

[5] conversations with Karen ปกาเกอะญอ musician and community leader Ker-Se-Tu Dinu เก่อเส่ทู ดินุ

About the artists

elekhlekha อีเหละเขละขละ is a collaborative, research-based duo formed by Thai diaspora artists Nitcha (Fame) Tothong and Kengchakaj, both born in Bangkok and currently based in Brooklyn. Their work explores subversive storytelling through non-hegemonic sound and visual archives, historical research, and experimental multimedia practices.

The name elekhlekha—a Thai word meaning chaos, entropy, and non-direction—reflects their commitment to breaking free from Western categorizations. Drawing on Southeast Asia’s political complexity, they merge oral histories and sound cultures with algorithmic composition to challenge traditional narratives and reimagine new modes of expression. Their work embraces decolonial methodologies, aiming to amplify suppressed histories and redefine cultural agency through sonic and technological experimentation.

Visit: elekhlekha.xyzFollow on Instagram: @elekhlekha