From the telegraph to AI, our communications systems have always had hidden environmental costs

Knowledge hub

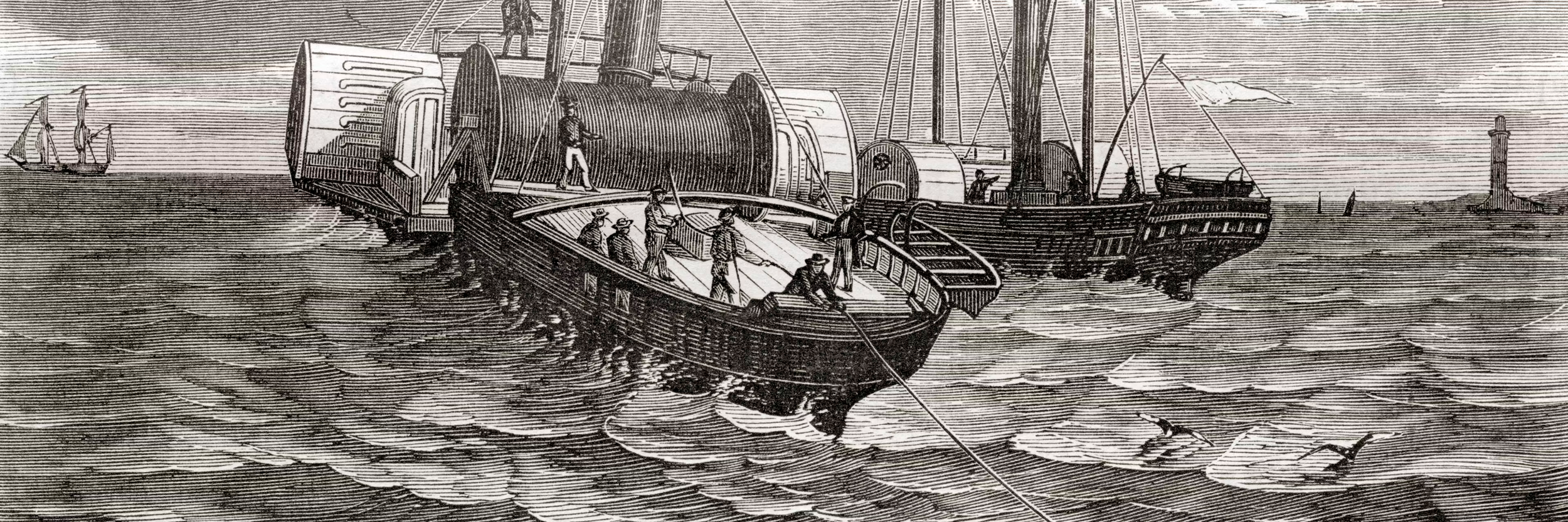

The first attempt to lay submarine telegraph cable between Britain and France. Universal History Archive/Getty

Article

Originally published in The Conversation • 07 Oct 2025

When we post to a group chat or talk to an AI chatbot, we don’t think about how these technologies came to be. We take it for granted we can instantly communicate. We only notice the importance and reach of these systems when they’re not accessible.

Companies describe these systems with metaphors such as the “cloud” or “artificial intelligence”, suggesting something intangible. But they are deeply material.

The stories told about these systems centre on newness and progress. But these myths obscure the human and environmental cost of making them possible. AI and modern communication systems rely on huge data centres and submarine cables. These have large and growing environmental costs, from soaring energy use to powering data centres to water for cooling.

There’s nothing new about this, as my research shows. The first world-spanning communication system was the telegraph, which made it possible to communicate between some continents in near-real time. But it came at substantial cost to the environment and humans. Submarine telegraph cables were wrapped in gutta-percha, the rubber-like latex extracted from tropical trees by colonial labourers. Forests were felled to grow plantations of these trees.

Is it possible to design communications systems without such costs? Perhaps. But as the AI investment bubble shows, environmental and human costs are often ignored in the race for the next big thing.

From the “Victorian internet” to AI

Before the telegraph, long distance communication was painfully slow. Sending messages by ship could take months.

In the 1850s, telegraph cables made it possible to rapidly communicate between countries and across oceans. By the late 1800s, the telegraph had become ubiquitous. Later dubbed the “Victorian internet”, the telegraph was the predecessor of today’s digital networks.

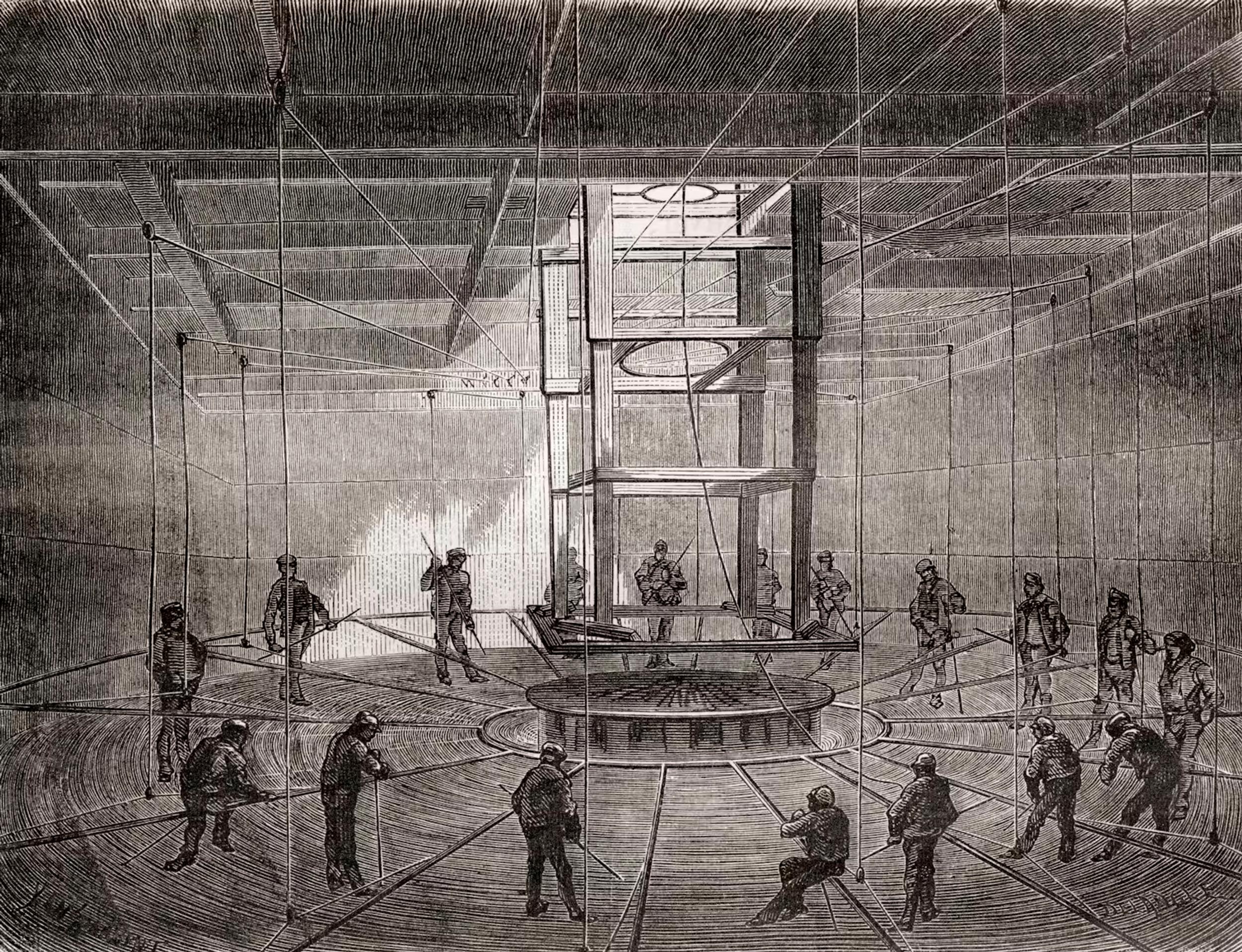

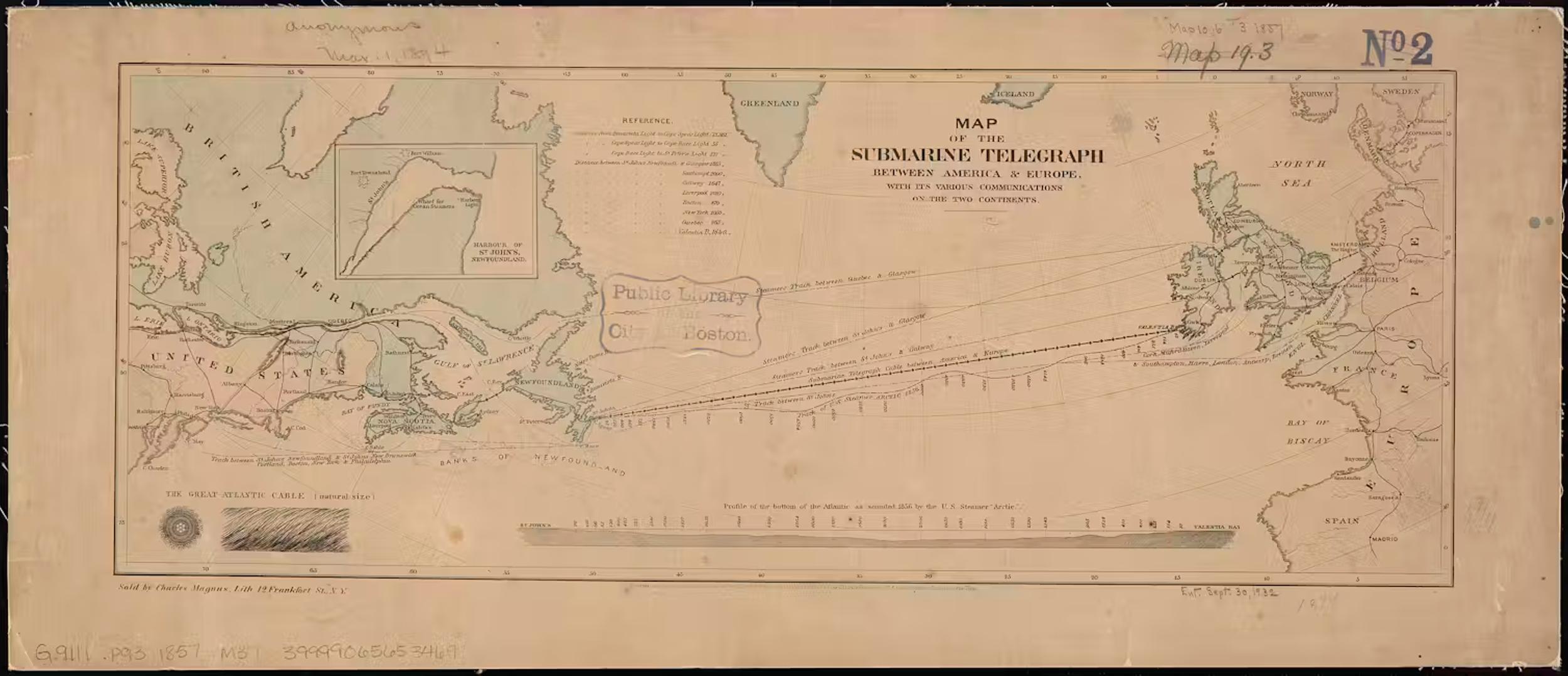

Building telegraph networks was a huge undertaking. The first transatlantic cable was completed in 1858, spanning more than 4,000km between North America and Europe.

Australia followed closely behind. European colonists created the first telegraph lines in the 1850s between Melbourne and Williamstown. By 1872, the Overland Telegraph Line between Adelaide and Darwin had been completed. From Darwin, the message could reach the world.

There are clear differences between the telegraph and today’s AI systems. But there are also clear parallels.

In our time, fibre optic cables retrace many routes of the now obsolete submarine telegraph cables. Virtually all (99%) of the world’s internet traffic travels through deep sea cables. These cables carry everything from Google searches to ChatGPT interactions, transmitting data close to the speed of light from your device to faraway data centres and back.

Historical accounts describe the telegraph variously as a divine gift, a human-made wonder, and a networked global intelligence, far from the material reality. These descriptions are not far off the way AI is talked about today.

Grounded in extraction

In the 19th century, the telegraph was commonly thought of as an emblem of progress and technological innovation. But these systems had other stories embedded, such as the logic of colonialism.

One reason European powers set out to colonise the globe was to extract resources from colonies for their own use. The same extractive logic can be seen in the telegraph, a system whose self-evident technological progress won out over environmental and social costs.

If you look closely at a slice of telegraph cable in a museum or at historic sites where submarine telegraph cables made landfall, you’ll see something interesting.

Wrapped around the wires is a mixture of tarred yarn and gutta percha. Cable companies used this naturally occurring latex to insulate telegraph wires from the harsh conditions on the sea floor. To meet soaring demand, colonial powers such as Britain and the Netherlands accelerated harvesting in their colonies across Southeast Asia. Rainforests were felled for plantations and Indigenous peoples forced to harvest the latex.

Australia’s telegraph came at real cost, as First Nations truth telling projects and interdisciplinary researchers have shown.

The Overland Telegraph Line needed large amounts of water to power batteries and sustain human operators and their animals at repeater stations. The demand for water contributed to loss of life, forced dispossession and the pollution of waterways. The legacy of these effects are still experienced today.

Echoes of this colonial logic can be seen in today’s AI systems. The focus today is on technological advancement, regardless of energy and environmental costs. Within five years, the International Energy Agency estimates the world’s data centres could require more electricity than all of Japan.

AI is far more thirsty than the telegraph. Data centres produce a great deal of heat, and water has to be used to keep the servers cool. Researchers estimate that by 2027, AI usage will require between 4.2 and 6.6 billion cubic metres of water – about the same volume used by Denmark annually.

With the rise of generative AI, both Microsoft and Google have significantly increased their water consumption.

Manufacturing the specialised processors needed to train AI models has resulted in dirty mining, deforestation and toxic waste.

As AI scholar Kate Crawford has argued, AI must be understood as a system that is:

embodied and material, made from natural resources, fuel, human labour, infrastructures, logistics, histories and classifications.

The same was true of the telegraph.

Planning for the future

Telegraph companies and the imperial networks behind them accepted environmental extraction and social exploitation as the price of technological progress.

Today’s tech giants are following a similar approach, racing to release ever more powerful models while obscuring the far reaching environmental consequences of their technologies.

As governments work to improve regulation and accountability, they must go further to enforce ethical standards, mandate transparent disclosure of energy and environmental impacts and support low impact projects.

Without decisive action, AI risks becoming another chapter in the long history of technologies trading human and environmental wellbeing for technological “progress”. The lesson from the telegraph is clear: we must refuse to accept exploitation as the cost of innovation.

With thanks

This piece was originally published by The Conversation and has been reposted with permission.

Jemimah Widdicombe

About the author

Jemimah Widdicombe leads the development of temporary exhibitions as Curator at the National Communication Museum (NCM) in Naarm/Melbourne, Australia. Her work focuses on the intersection of culture and technology, and is underpinned by foundations in human interaction research & design and cultural production.

Jemimah’s curatorial career spans over a decade of interdisciplinary projects, including strategic exhibitions, collections and content roles at Museums Victoria and the University of Melbourne, coupled with extensive experience in digital research, education and cultural program coordination in Kanaky New Caledonia and France.