Lillian Schwartz: On human-machine relationships, nature and noise

Knowledge hub

Placeholder

Emily Siddons, Co-CEO and Artistic Director

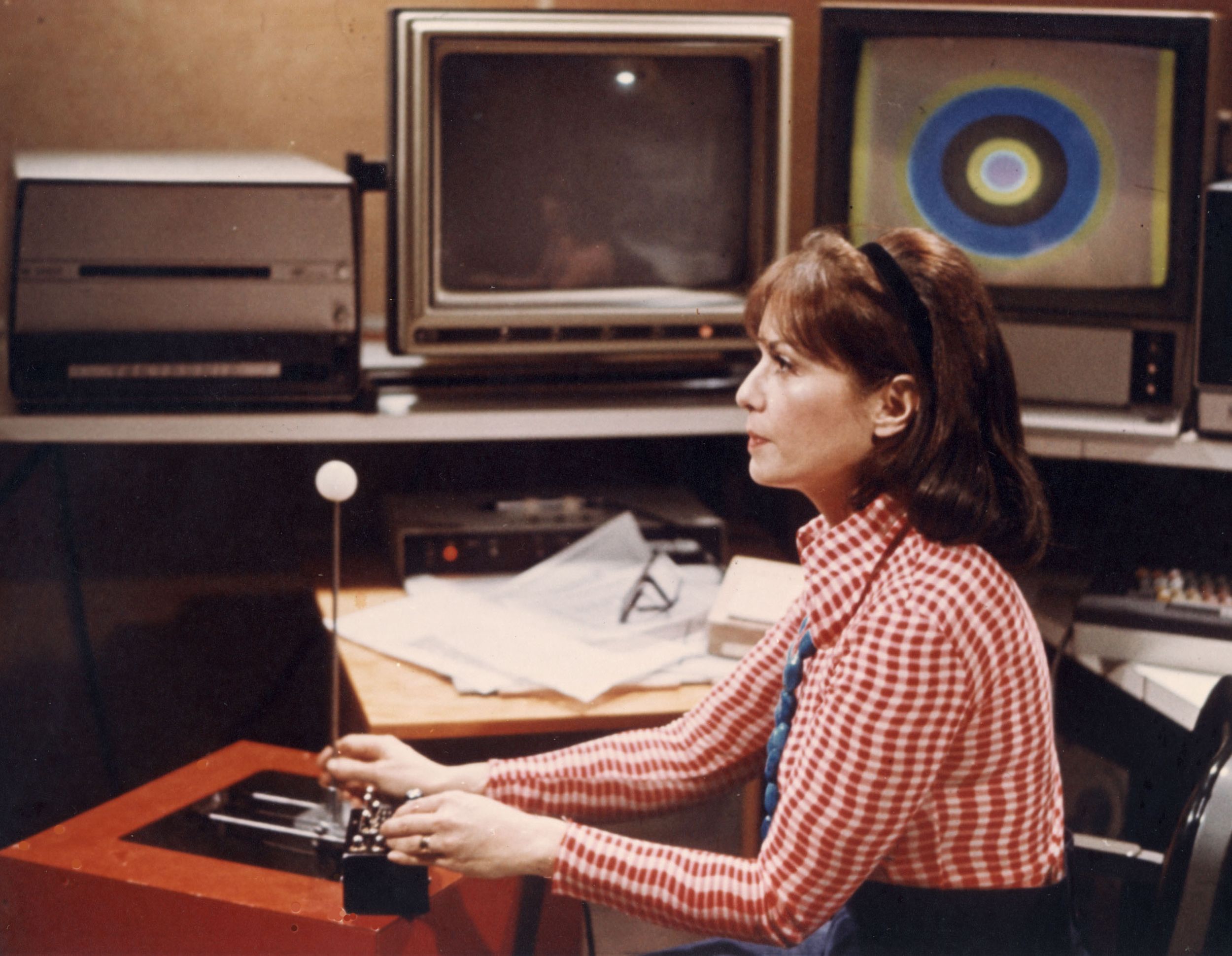

Lillian Schwartz, the first female resident of the Bell Labs, was a pioneer of computational media and digital art in the 1960s and 70s. Her work came to define a movement that she called “Pixellence,” which uncovered new modes of artistic practice using computer graphics, groundbreaking animation techniques, and new video and editing effects.

Her art, created years before the development of the graphical computer interfaces we know today, raised questions around human-machine interaction, authenticity and artistic expression through emerging technologies. In many ways, her work prefigured the questions we face today regarding Artificial Intelligence, authorship and human obsolescence.

"...the machine had to keep pace with me — just as I learned that I had to grow with the machine as its scientifically oriented powers evolved.” —Lillian Schwartz, 1992

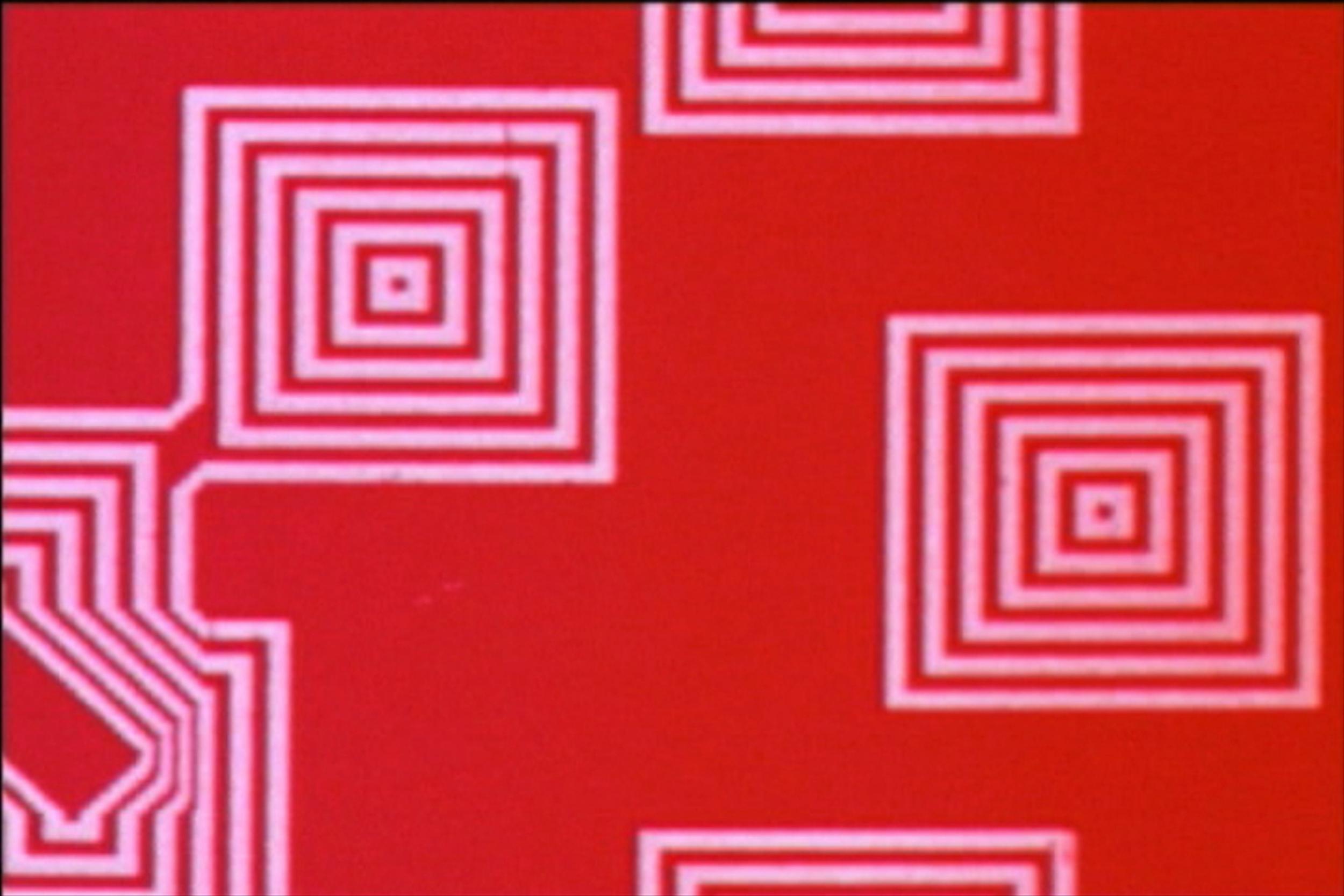

The Glitch Aesthetic

Schwartz’s deliberate disruption of digital signals and computational systems drew attention to their predisposition to interference or noise. During the beginnings of industrialisation, technologies were designed to remove interference from the channel in an effort to create a clear signal. Though as Hillel Schwartz describes, artists and theorists soon came to find that noise offered fertile ground for experimentation and discovery.

“Out of studies of intelligibility across phone lines and through radio waves will arise information theory, which redefines noise as at one intrinsic and revealing.” — Hillel Schwartz, From Babel to the Big Bang and Beyond, 2011

As new computing technology was released, Schwartz found ways to embrace the glitch through pixelated images, broken sound, distorted video and fragmentation.

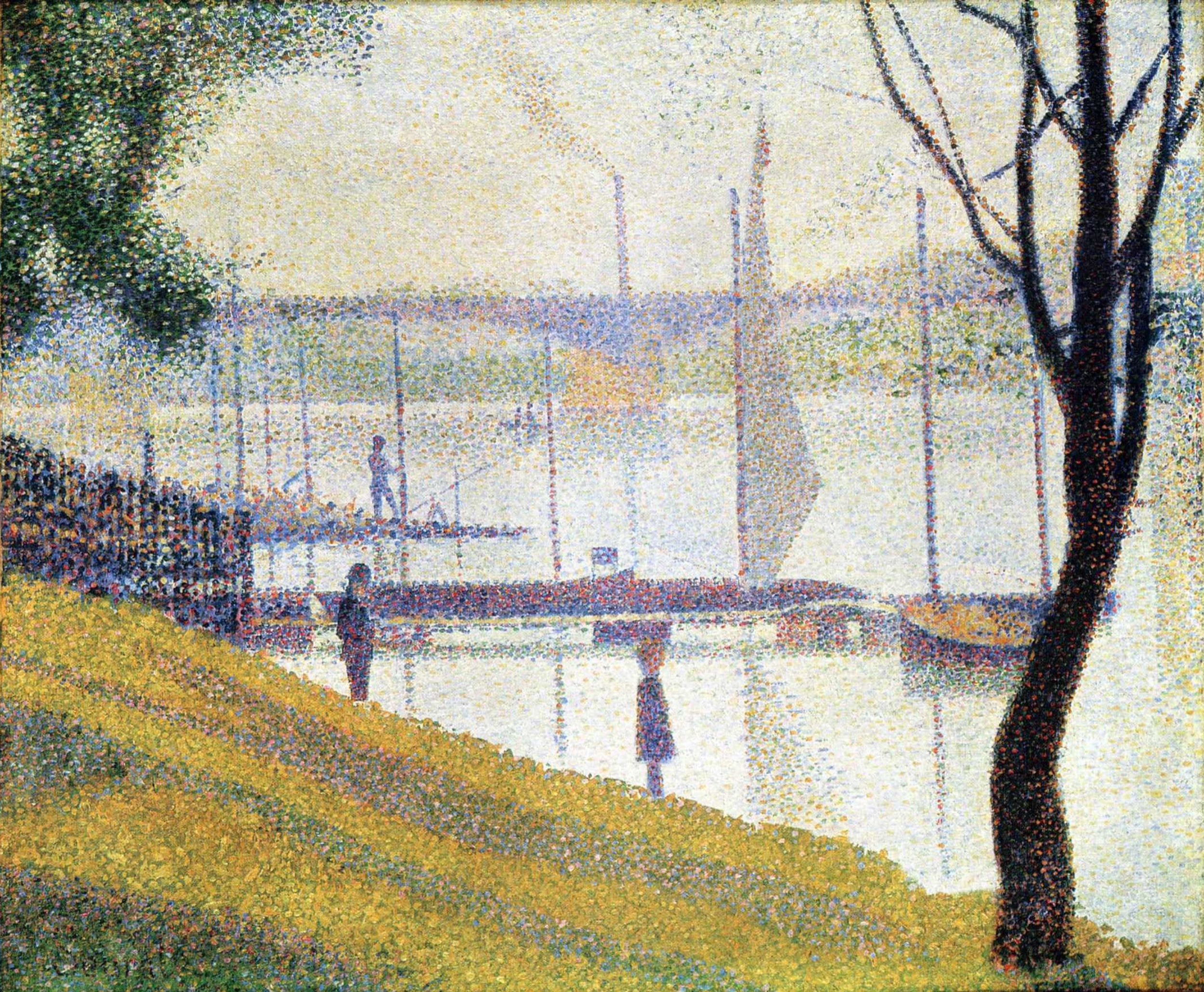

Her artwork, Pixillation, exploits the tension between computational processing and the handmade. Schwartz often drew from art history and took particular inspiration from the work of George Seurat, a French post-Impressionist artist who created Pointillism. What would appear as a series of dots up close, would reveal a fully formed scene when viewed from further afield. Schwartz was fascinated by how she could create and manipulate dots with a machine.

“The dots of the screen may not flake like mis-matched paints, but there is a definable chemistry behind the electronic palette, a combination of data, logic and equations…” — Lillian Schwartz, 1992

In Signal to Noise, Schwartz’s artworks sit in dialogue with Nam June Paik’s Internet Dream and JODI’s My%Desktop. These artworks build on Schwartz’s early experiments to explore intentional fragmentation and system malfunctions associated with internet cultures that would emerge years later. For Paik, he foresaw an 'Electronic Superhighway' where technologies would connect to global networks, predicting that the internet would be more complex and erratic than the utopian picture of free-flowing information that emerged in the 1990s. This feeling of chaos is most prominent in JODI’s artwork My%Desktop, which depicts corrupted desktop interactions that abstract the user interface and unfold simultaneously over four screens. However, it is Eryk Salvaggio’s SWIM that sits directly opposite Schwartz’s artworks Pixillation and UFOs, that brings this topic into contemporary focus. SWIM poetically captures our relationship to digital noise today and the disintegration of our collective cultural memory. As Nini Shipley swims in slow motion amidst failed AI-images from glitched diffusion models, the flood of information makes it ever more apparent how noise infuses everything in our digitised experience of the world today.

Human-machine relationships

As a pioneer of early digital art and computational media, Schwartz explored how digital mediums could redefine concepts of authorship and creativity. She explored the relationship between artist and machine, developing new software tools and computer algorithms designed to manipulate and abstract colours and forms.

Her artworks experiment with early interactivity, questioning ideas around authorship and the human-machine relationship in artistic processes. Despite its randomness and computer-generated elements, her artworks retain a strong feeling of authenticity and the human touch feels ever present. Data, algorithms and archives form the foundation of AI systems today. It is the loss of data – the errors, glitches and unintended signals – that make us reflect on what is absent or even decaying. The resulting artworks manifest a beautiful chaos, blending organic shapes and forms with computer-generated images and data manipulation. Schwartz presents a compelling vision of the computer as both collaborator and co-author.

“A computer is never lifeless. It hums as if it were cogitating some primordial secret that it will tell us only if we nurture it.” — Lillian Schwartz, 1992.

Considering broader environmental contexts, begs the question of what happens when nature or organic forms are filtered through the lens of technology? Schwartz’s 2D artworks, Landscape and Nightscene, employ a technique of digital painting, where light is digitally manipulated to distort depth and form. This in turn re-interprets nature and cities and subjects them to computation, synthesising these forms to convey a dreamlike quality or feeling of otherworldliness.

Symbolically, this relationship is most pronounced in her artwork Mandala, which references a symbol associated with spiritual harmony and interconnectedness. Subjecting this symbol to computational systems and patterns, deliberately introduces error, noise and disorder. This in turn reveals the function or inevitability of noise, or at least a world more complex than technologies can contain.

Lillian Schwartz’s artworks represent a remarkable body of research that continues to provoke questions that are increasingly relevant today. From a contemporary standpoint, we can examine the profound shift in human-machine relationships and consider the role technology plays in shaping our collective experience and imagination. The increasingly fragmentary nature of culture across different media types, networks, programs and interfaces, creates a dichotomy between artificial and natural memories. In this complex landscape, delving into and weaving through the noise can offer the most fertile ground for new ideas.