Machine Listening

Knowledge hub

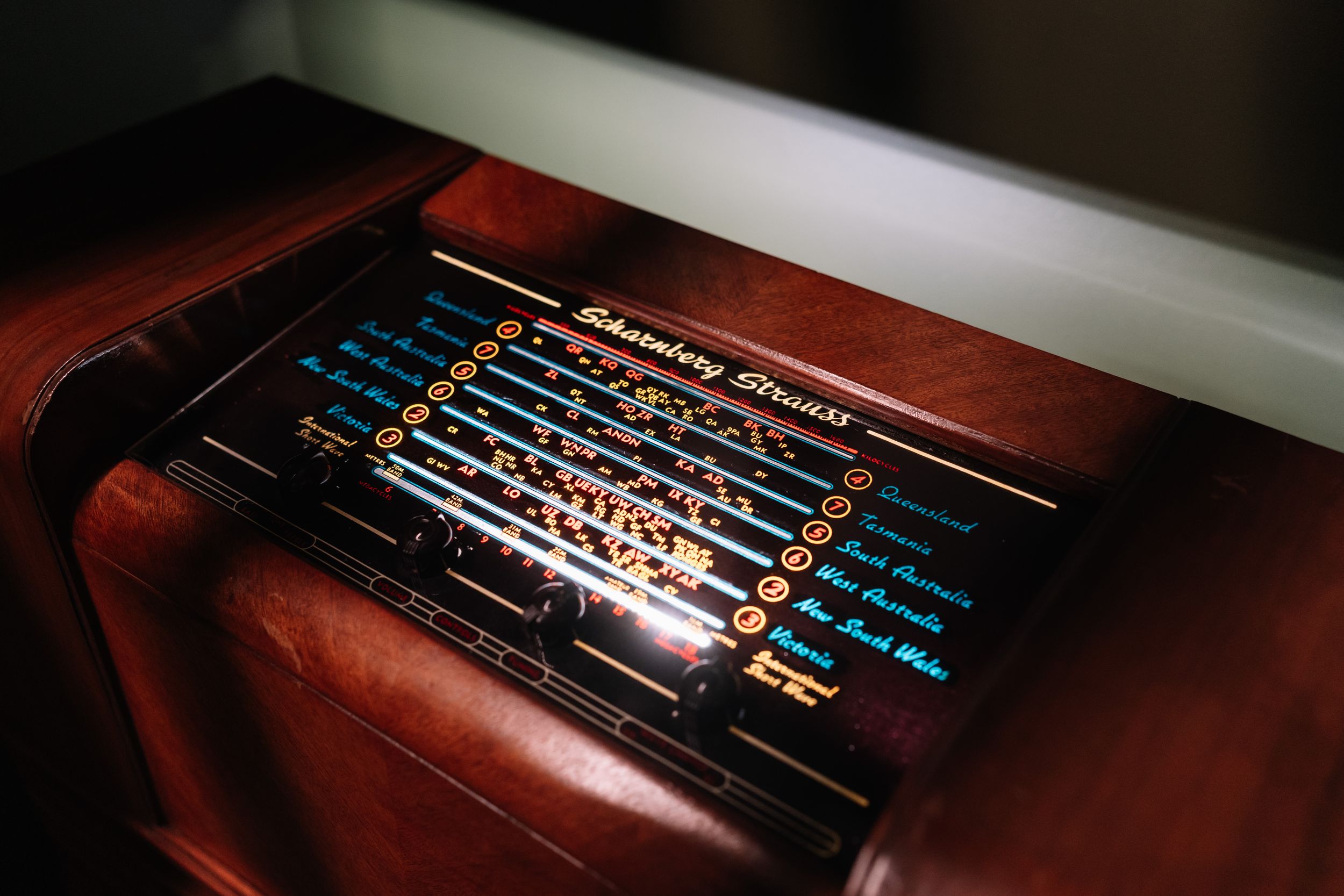

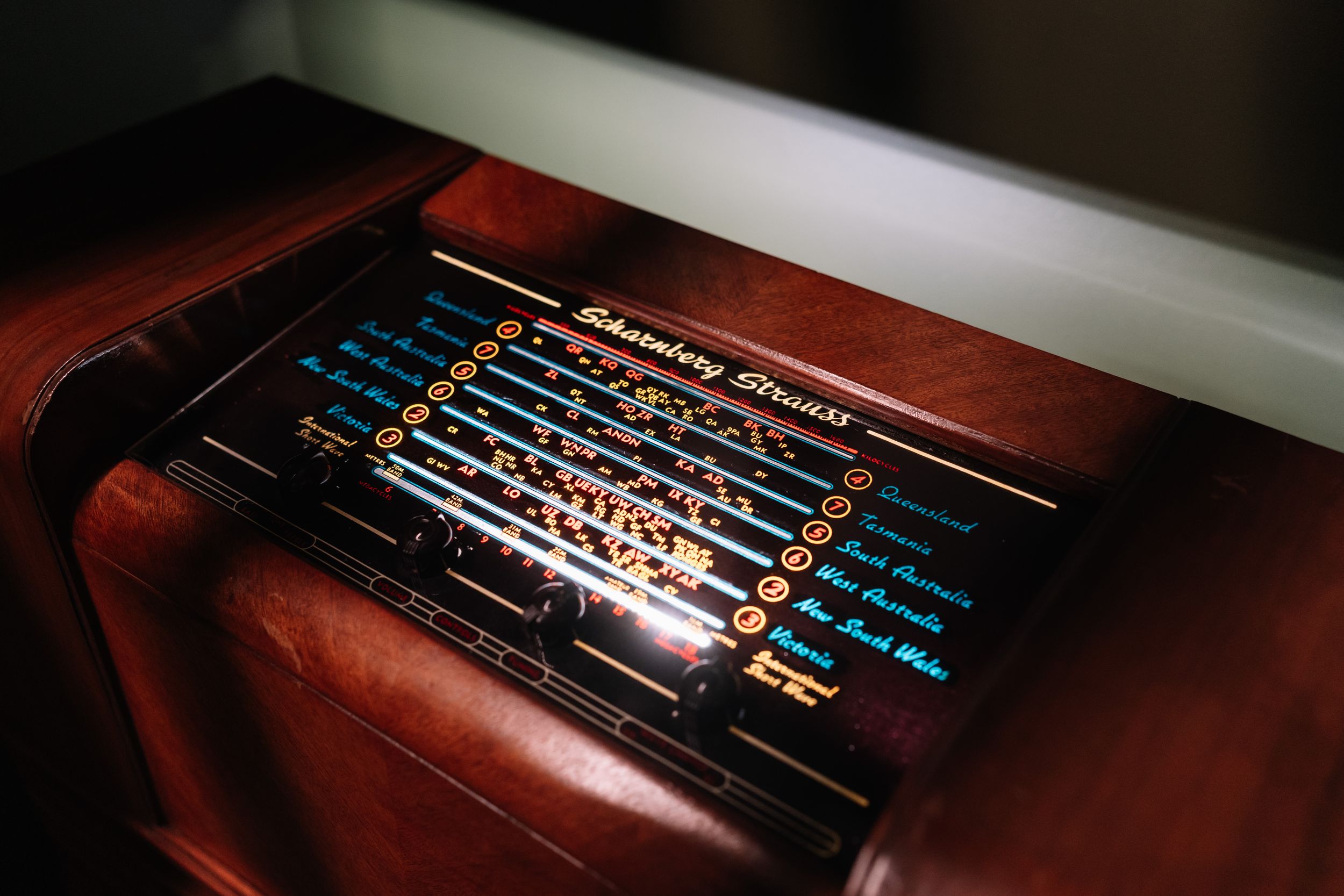

One of the radios in Voyce Walkr. Photo by Phoebe Powell, 2025.

Essay

Voyce Walkr, 2025

Multi-channel audio, 4 vintage radios, analogue synthesiser Voices: Orin Howard, Jasper Dockray, Beatrix Hughes Stern, Vyvyan Hughes Stern, Jenny Hickinbotham, Francis Plagne – and their clones Commissioned by NCM

About the artwork

Voyce Walkr by Machine Listening is a reimagining of Russel Hoban’s incredible 1980 novel Riddley Walker, updated, reworked, and distilled in response to our technological present, and then staged at the NCM as an installation for four vintage radios.

For the unfamiliar, Riddley Walker has a cult following but isn’t as widely known as it deserves to be. Hoban began working on it in the mid 1970s, in the middle of the Cold War, in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis, and on the brink of Thatcherism in the UK and Reaganism in the US. In the novel, nuclear war has wiped out most of civilisation. The environment is ruined, advanced technologies have disappeared, and after some 2000 years the human societies that remain - at least in what was previously England - are shadows of their former selves. Life is Hobbesian and brutal. Violence and death are everywhere.

What Hoban does against this relatively generic, even trope-ish backdrop is truly weird. Society is organised around a strange mythology, based on fragments of a discovered text about the Christian martyr and former Roman general Saint Eustace, fused with half-remembered accounts of the war. Even stranger, this mythology circulates via the institution of travelling puppet shows, based on the old English tradition of Punch and Judy. Finally, the whole novel is written by a twelve-year old narrator in an invented dialect: a kind of future and degraded English, full of neologisms, colloquialisms, inconsistent and irregular spellings.

It was Hoban’s use of language that immediately spoke to us when we were invited to make something for Signal to Noise. Riddley Walker is hard to read at first. But what starts off impenetrable quickly turns to poetry. Lots of commentators have pointed to the similarities between Hoban’s English and Chaucer’s. We were drawn to that aspect of the book, partly as a formal and experimental device, but also because Hoban’s noisey language is directly related to themes of technology and (ir)responsibility.

For Hoban, writing in the 1970s, the obvious dystopic technological horizon is nuclear warfare. But thinking with the novel in 2025, that doesn’t seem as relevant any more. Not because it’s no longer possible. More because it’s no longer necessary. And largely because of what’s been happening in techno-science, and especially computation, since Riddley Walker was published. Philosopher of science and technology, Paul Virilio was already writing in 2000, for instance, that 'it no longer takes a war to destroy the reality of the world.’

That just feels obviously true now, an era characterised by info-and-misinformation overload, silos, bubbles, and the total domination of our collective media environments by Big Tech oligarchs and their presidential puppets; or maybe it’s the other way round. Either way, this same (mis)infotainment environment is also literally killing the planet, one post or prompt at a time. And the only solution on offer, other than literally escaping to Mars, is apparently more of the same.

“Good Time which I mean evything good an evybody happy an teckernogical progers movin evything frontways farther an farther all ee time.”

More and better techno-capitalism. The ever receding fantasy of green AI. The hubris and neo-imperialism of geoengineering. Nature as a service. If Hoban were writing Riddley Walker now, he wouldn’t need to imagine nuclear war. He could just imagine the continuation of business as usual.

That’s where our reworking of the novel’s central mythology begins. What Riddley calls ‘the Eusa story’ (riffing both on St Eustace and the USA, who the reader presumes initiated the Bad Time) becomes ‘the User story’ in our retelling.

The User Story

Wun.

When Mr. Proffet was Big Man of Inland, ey had evythin profitable. Ey ad thinkin macheyans, weather on command, and evythin like that. User was a knowin person, real quick an clevver in imho. User was workin for Mr. Proffet when there came droughts and floods all roun, makin Crisis. User sed to Mr. Proffet, "Now we'll need All-Rivums of Control. Wyl need macheyans at predic the skys and macheyans at change thee earth as well, and wyl need Big Nummers and infomayshun wars."

In Hoban’s novel, Eusa is an ambiguous figure: responsible for inventing the atomic bomb, but also manipulated by the mythic Mr Clevver to deploy it. This is the same ‘clevver looking bloak’ who, in the novel’s opening chapter, convinces a starving couple to kill and eat their baby in exchange for the gift of flint and steal.

These themes of manipulation, responsibility and agency in relation to technology are literalised in the novel in the institution of the puppet-show-as-propaganda and the figure of Mr Punch, who has also murdered a baby or two in his time.

Punch is rubbin his hans in joy of it he ses, "Um. You cant beat a good banger."

Up cums Jooty with the fryin pan and the babby which its a littl pink piglt. Jooty ses to Punch, "Youve et that swossage havent you."

Punch ses, "O no I dint."

I sed, "O yes you did."

Apart from his famous catch-phrases, distinctive hooked nose and outfit, Punch is famous for his high-pitched voice which, in traditional seaside Punch and Judy shows, is produced using a small metal and reed device held in the puppeteer’s mouth, called a ‘swazzle’. Since we knew we were making a radiophonic update of Hoban’s novel, this rudimentary form of voice manipulation seemed important to think with and develop.

In some of our conversations about this work, we imagined it being set hundreds of years after the events in the book. Having accepted the devil’s bargain, technology is starting to evolve again, as more and more parts and materials are salvaged from digs in the ruins of our present. The institution of the puppet show is in the process of being adapted for rudimentary radio networks, on which the User story is broadcast daily. This is the ‘voyce walking’ of the work’s title.

Dry as an bone it were again that mornin.

I put my han in thee dust I reach-ed down and come up with some thing it were a show figger, a puppit like em ones in thee User show frum way back when. Woodin head and hans and the res of it clof: all of it gone blac and the show mans han sill in it. Cutoff jus a litl way up the rist. An next tit in a lil bag there wer two curvit bitsa iron all eld together, i member they calld it a swozzle or swerzzle or summit. Like fur voyce walkin but real simple like.

In the gallery, Voyce Walkr is staged using two pairs of vintage radios from the NCM’s collection. One pair foregrounds narrative: 11 scenes compressed, rearranged and distorted from Hoban’s novel as raw material. The other pair presents noisier, more abstract and fragmentary treatments: closer to avant-garde poetry or experimental music, though the distinction is not so neat. We have introduced new language and embedded contemporary references, including to billionaire venture capitalist Mark Andreeson’s deranged and symptomatic Techno-Optimist Manifesto. The narrators you hear are all clones, voice puppets, mostly derived from the voices of our own children but performed by us. The other sounds were made with a 1970s analogue synthesizer, set to ‘follow’ the cloned speech, and vice versa.

One of the references we had in mind were the radio plays of the 1930s-1950s, where horror was a particularly popular genre: Orsen Welles’ adaptation of HG Wells’ War of the Worlds for Halloween 1938 being one notorious and influential example. Another reference would be the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, which was founded in 1958, and pioneered the kinds of electronic, experimental and computer music which we often still hear as the ‘sound of the future’ today.

We are not the first to adapt or be inspired by Riddley Walker. In 1984, Hoban himself developed the novel for stage with the legendary and anarchic Impact Theatre as The Carrier Frequency, yielding an amazing album by Graeme Miller and Steve Shill. In 1999, the performance was revived again, and there have been many other versions and references across theatre, music, and film.

Presented on pristine radios from the 1930s-1970s, Voyce Walkr deliberately reimagines and abstracts Hoban’s original, this time for the gallery. It is meant to evoke radio’s various golden age(s) at the same time as the story imagines radio as a crude post-apocalyptic medium, far in the future. Time has been deliberately scrambled. Cloned children tell of coming ‘infomayshun barms’ on vintage radios. Old stories of dystopian futures tuned in to the anxieties of the present.

Orfing ses, "Here we come roun agen its a fools circel. If you dint do no tekno-logical velopmint an kept ee coalanoil an rain an split thee Bloo Drop’t then whyd you say you did when you wrote down that story? Dont cut your froat now or somewun I know wil have a bloody finger."

User ses, "If I hadnt some one else wudve. People, like sharks, ey grow or dy. Tekernlogical velopmint is growf, an change, an pro-guess. Teknology is thee glory of human bishon and chievement. Evything good cum frum growf an growf can’t be wifout your knowin of em or makin em. Then its on you innit. Hevvy on your bac for ever. Thats my Las word this nite.”

An I steps back from ee trans-mitter an takes me kwipment out fum unner me tung an ses to Goodparley, “That’s the way to do it” an steps on down owt of ee tower.

About the artists

Machine Listening is an artist-research collective established in 2020 by Sean Dockray, James Parker, and Joel Stern. The group explores the political and aesthetic dimensions of sound and listening in the age of big data, focusing on how technologies like voice assistants, smart speakers, and AI systems capture, analyze, and respond to sound and speech. Their work interrogates the implications of these technologies on society, culture, and individual agency.

Joel Stern is an artist, curator and researcher living in Naarm/Melbourne whose work focuses on practices of sound and listening and how these shape our contemporary worlds. He is a Research Fellow at RMIT School of Media and Communication, an Associate Investigator at ADM+S, and between 2013 and 2022 was the Artistic Director of Liquid Architecture.

James Parker is an Associate Professor at Melbourne Law School, who works across legal scholarship, art criticism, curation, and production. He is an Associate Investigator with ADM+S, a former ARC DECRA fellow, former visiting fellow at the Program for Science, Technology and Society at the Harvard Kennedy School for Government, and sits on the advisory board of Earshot , an NGO specialising in audio forensics.

Sean Dockray is an artist and writer whose work explores the politics of technology, with a particular emphasis on artificial intelligences and the algorithmic web. He is a Senior Lecturer in Fine Art at Monash University, a founding director of the Los Angeles non-profit Telic Arts Exchange, and initiator of knowledge-sharing platforms, The Public School and AAAARG.ORG.