Possible Noise

Knowledge hub

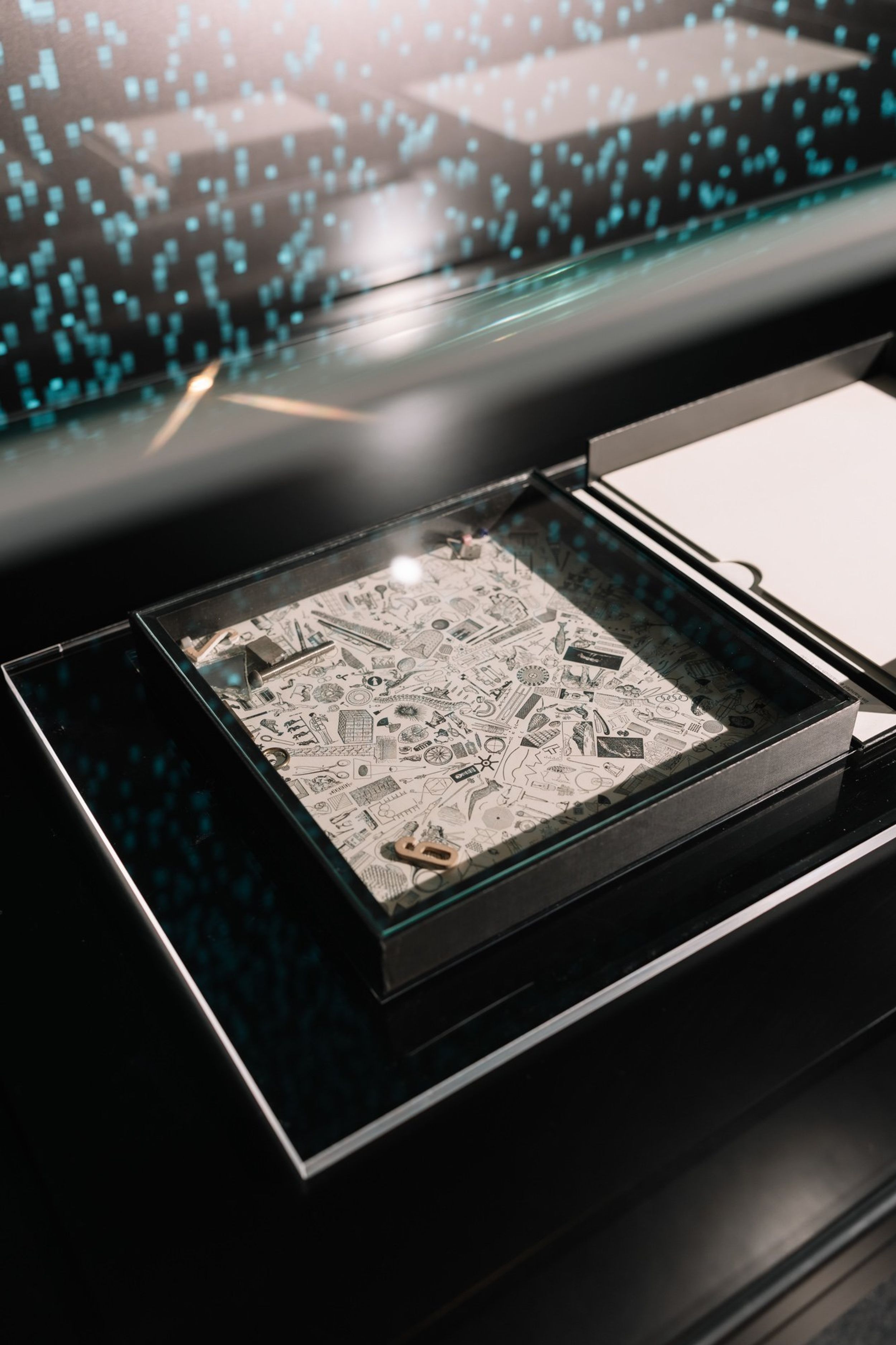

Internet Dream, Nam June Paik. Seen at Signal to Noise, 2025. Photo by Phoebe Powell.

Possible Noise • Curator Notes

Written by Eryk Salvaggio

In Signal to Noise, visitors are invited to explore how artists use noise to challenge, distort, and redefine communication technologies, engaging with the chaos and beauty that emerges from this exploration. The exhibition delves into the intersection of art, sound, and technology, where noise disrupts the clarity of messages and blurs the boundaries between the digital and physical realms.

In this article, curator Eryk Salvaggio takes you on a walkthrough of the exhibition, where each artwork offers a unique perspective on how noise shapes our understanding of technology and our relationship to it.

A guided tour of Signal to Noise with Eryk Salvaggio

In the age of computation, the role of noise — or at least, the close-enough approximation through pseudorandom numbers — has been the bulwark against the rigid and orderly logic of mathematics and prediction. Leslei Mezei, writing for Jasia Reichardt’s “Cybernetics, Art, and Ideas,” puts forward a theory of the computer-generated image that would be just as accurate for describing generative AI, with a few million more pixels:

“... Constraints impose the unity, the overall structure, or in the terminology of ‘information aesthetics,’ the macro-aesthetics of the picture. Were we to repeat the experiment any number of times, we would get a larger number of variations, some more interesting than others, but the overall structure would remain recognizably the same. The program embodies the generating rules, or the algorithm, with which random selection is capable of producing an infinite variety of similar pictures. (165)” — Leslei Mezei

This seemingly paradoxical point of “an infinite variety of similar pictures” is all too often lost on us in discussing generative AI. When Lev Manovich writes that “We can now, in principle, create an infinite museum filled with endless AI-generated images that simulate artworks from every period in history for all genres, artistic techniques, and media,” he is, in principle, wrong. The generative AI system is just as constrained by data as Leslie Mezei’s computer was in 1971. There is just more data through which to constrain the possibilities of noise by turning to reference, and to specific, commonly accepted regimes of image-making.

Generative AI is, after all, a noise reduction technology. It just so happens to produce an image at the end of that process. It dissolves training data by introducing noise in a sequence of steps, storing the path of this noise to memory. When prompted, it plays these steps in reverse, applied to random noise, in a bid to denoise it into a statistically centered outcome based on accumulations of images related to the prompt. This reliance on noise is what produces the illusion of creativity in the system, a means of creating variety. But it is always constrained by data, by historical reference, by language.

It is constrained to an overdetermined process which, unlike human creativity, centers itself without opportunity to shift its strategies. Creativity in the machine cannot exist; it follows a set regimen of steps for noise reduction. It will produce images that inevitably center pattern, not possibility: generate an "infinite museum," and images will soon reveal their own patterns, their own logic, within 9-12 pictures. This is not some deep, abstract thing. You can try it yourself, and see what happens. This infinite museum soon becomes infinitely dull and repetitive.

A "Post-AI" Art Exhibition

It is this structure of generation from which Signal to Noise takes its cues as a “post-AI” art exhibition. It is structured as a historical lens on artists who worked with the unique affordances of noise in given communication technologies of their era, embracing the breakdowns that pushed computational rigidity to its limits. In some sense, it shows how artists are free to work with noise to push boundaries, reimagining the systems they work within, a capacity of human art that is at odds with the art-making as defined within automated image generation systems.

In this way, we look at AI in hindsight, rather than the forward-looking lens of utopian hype or doomer panic. Instead, Signal to Noise looks at AI as one more media format designed to reduce noise — that is, unpredictable and unwanted intrusions into “clean” media signals. Artists have been introducing noise into channels for as long as we have had technology in which to intervene, through technical or imaginary acts.

Universal Machines

Consider Universal Machine, George Brecht’s 1965 take on the rigid mathematics of computational systems. Brecht places his assemblage of images and text — cut out from magazines — into a cardboard box. The instructions tell us to shake this box to generate new, random patterns (though bound, as always, by the constraint of his pre-selected vocabulary). Arguably, Brecht’s box is just as generative as any AI system: a scattering of data points, activated by the shaking of a “black box” to propose new structures for whatever the shaker has intended. Brecht’s instructions even seem to echo the hype of Silicon Valley: “Need a friend? Shake the box.” The box can even write novels: shake the box, open it, and that’s chapter one. Do it again for chapter two. Use Number 18: “Travel Itinerary.”

Nam June Paik’s “Internet Dream” embraces the noise of information overload, with Paik himself pioneering the use of magnets onto televisions to distort the carefully calibrated signals of cathode ray tubes. In JODI’s My%Desktop, artists insert friction into the friction-reducing site of the computer interface. The graphic user interface of desktop computing was designed to constrain the options of computation while making them more readily accessible (just think if you had to write a command line query for every email). JODI’s work inverts this, turning the desktop interface into a site of contention and error, estranging us from its simplicity and use for “productivity.”

Machine Sees More Than it Says, from artist Mimi Onuoha, hints at the origins of computer vision and image generation, “a sketch of a computer's imagining of itself and the courses of development which formed it, hinting at processes of resource extraction, transport, technical advancement, interfaces and labor.” The archival footage is a document of how we have allowed computers to produce images of themselves: each scene is the result of a computer’s existence as a product (the computers and screens being filmed) or political purposes (the reasons they are being filmed to begin with). As such, the images in this piece evoke a powerful arrangement of order and control that elides the chaotic origins, histories and purposes to which they were meant to be used.

Beautiful Sounds

In contrast to this order, New York-based Thai artist duo elekhlekha อีเหละเขละขละ present “The beautiful sounds are gathered together in one cluster,” a work which embraces the shifting tonalities and relationships that emerge when a listener attends to noise. This is a mix of 32 speakers suspended from the ceiling and transducers triggering assorted aluminum objects. As percussive synthesized gongs are triggered along with transducers rattling tin cans and other metallic objects, they blur into a meditative drone. But they soon shift into discernible, complex rhythms and tonalities depending on one’s position and willingness to listen.

The auditory and political message come to overlap: the work is a challenge to the idea that the music of gongs in the artist’s home, Thailand, is described by Western observers as “noise.” Position in relation to noise is what defines it, far more than any inherent tonal or communicative quality. The question of order and stability is relative to the desire for change and transformation. What fits into our patterns is order, what resists them is noise.

From Australian artist Rowan Savage, the transformation comes about in another way: the boundaries between the sounds of human and natural language. Using a home-trained AI system to convert samples of Savage’s voice and field recordings of crows, the sonic texture of crows transforming into human vocals creates a distorted audio track punctuated by natural crow calls and the question Savage repeats on loop: Who am I? For me this speaks to the internal dissonance of noise in our heads, the cognitive friction that emerges from our desire to separate from the technological and natural worlds in which we are immersed — but also what happens when we abandon claims to be separate, the friction that rises in attempts to defend our ego if we try to become something more fluidly connected.

Direct Communication

There is a moment in the show — just after “The beautiful sounds are gathered together in one cluster,” that one can stop and look back at the path the visitor has just traveled. And from there, the “noise” is revealed as, paradoxically, a set of isolated, structured zones: Onuoha, JODI, and Paik. Overwhelming at first, complex up close, now isolated in space within their own grids, sortable in our heads. That these zones are apparent after you move through them reflects an innate psychology of moving through noise into order. Order appears in hindsight — a result of sense-making. The patterns become clear, the sounds in the din have been isolated. We make sense of things in our own way.

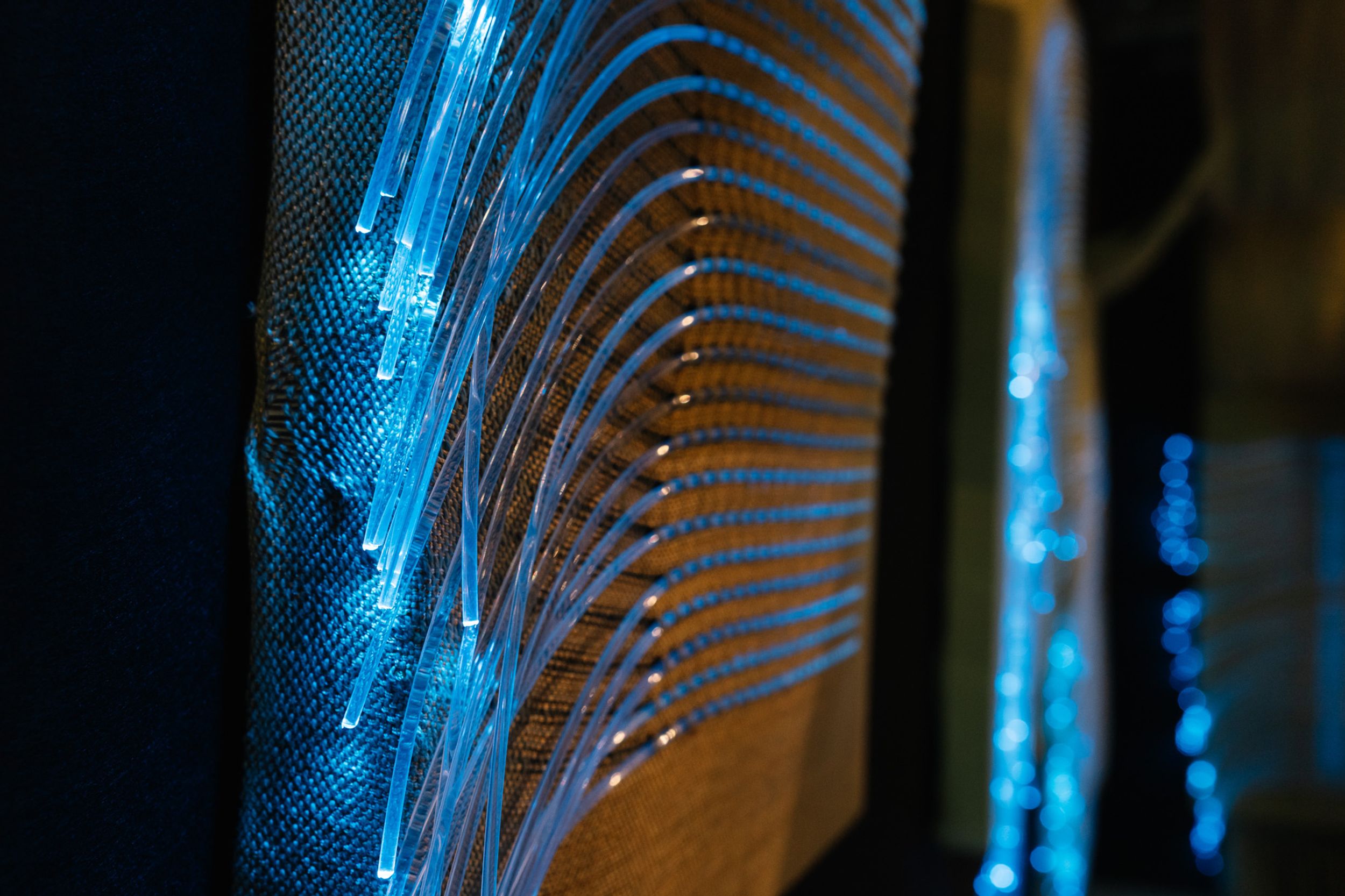

While it is the first piece in the show, it is worth discussing Craftworks “Ancient Futures” as the endpoint of this attempt at sense-making. Craftwork, another New York based duo, creates textiles entwined with fiber optic cables that capture colored light. Visitors are also offered a telephone to speak through, and voices are analyzed for key words and tones that come to be represented as colors in the cables. As more people contribute over the duration of the exhibition, the colored lights of past recordings will be replayed, weaving these stories into the textiles.Ancient Futures anchors us in the most basic form of communication, that which takes place when people gather together to weave together, to chat, to share stories. The textile (itself evocative of computation’s origins in looms) connects this basic interpersonal communication to the escalating abstractions of communication technologies: the telephone, AI. The voice shapes the signal, and yet, the voice dissolves into the system. Noise can be directed in all kinds of paths. The text of the message disappears, the machine interpretation lingers behind.

As you exit Craftwork’s cavern of textiles, you will encounter the exposed threaded tapestry of telephone patch cabling hidden behind the removed back panel of a telephone switchboard from the 1920s. Operators, too, weaved communications through wires — a fabric capped by plugs to form circuits in a constant shuffle by human operators, connecting voice to voice in all directions. Traveling through these wires would have been the incessant din — here, of Australian voices dialing through switchboard operators.

Freedom of Choice

Between the two is a quote from Cecile Malaspina’s Epistemologies of Noise:

“We will someday come to see noise as an inescapable freedom of choice.” — Cecile Malaspina

It’s an echo of Claude Shannon, whose 1948 Shannon-Weaver model for communication systems occupies a wall opposite JODI’s glitched desktops. The lines of the message are concentrated by the signal source, dissipating as they move from the source to the intended receiver. By the end of the process, our “message” is a scattered array of dots, the message obliterated in the media mess.

“Information is, we must steadily remember, a measure of one’s freedom of choice in selecting a message. The greater this freedom of choice, and hence the greater the Information, the greater is the uncertainty that the message actually selected is some particular one. Thus greater freedom of choice, greater uncertainty, greater information, go hand in hand.” — Claude E. Shannon

Noise is Possibility

More information, more noise. More noise, more freedom to choose. And then what? It's the hope of the curators that this exhibition mirrors that process of sense-making: moving the visitor from overwhelm to detail, then allowing a greater view of the whole. Making sense of the information that comes to us is an exercise in focus and attention, a cognitive flexibility of scoping in and then stepping back, reassessing the whole in the context of its individual parts. I think that is the type of experience that Signal to Noise provides, and the kind of attention it rewards.

Signal to Noise runs at the National Communication Museum (NCM) from 12 April to 11 September 2025.

About Eryk Salvaggio

Eryk Salvaggio is a new media artist and researcher exploring the social impacts of AI through creative misuse and critical dataset practices. A Visiting Professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology (New York) and an alum of the Australian National University, Eryk collaborates with Harvard’s metaLAB and the Siegel Family Endowment, blending art, design, and research to challenge dominant technological narratives. His work SWIM is currently on display in Signal to Noise, an exhibition he co-curated with Dr Joel Stern (RMIT University and ADM+S) and Dr Emily Siddons (Co-CEO and Artistic Director, NCM).

See more of Eryk’s work on his website.